W 45th

The City of Cleveland has an estimated 15,000 vacant buildings, including 8,000 vacant and distressed houses. These ghost structures bear silent witness to the Cleveland’s changing fortunes and to intimate experiences of life and loss in the city’s working class neighborhoods.

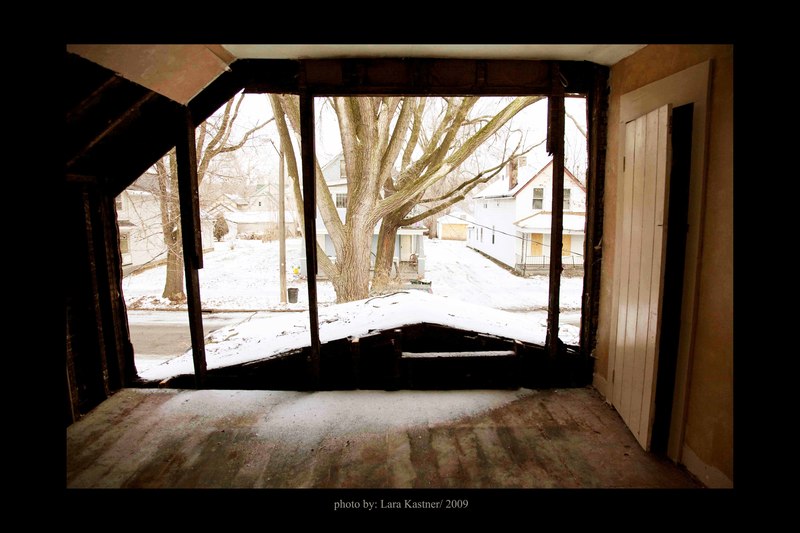

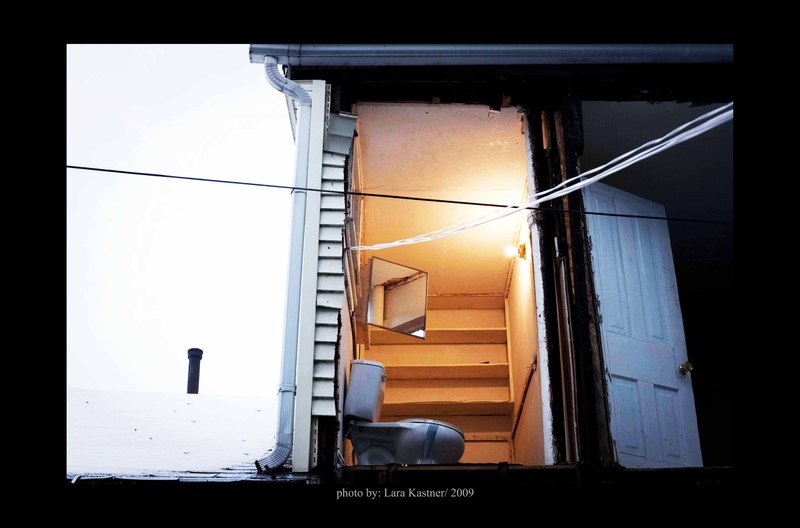

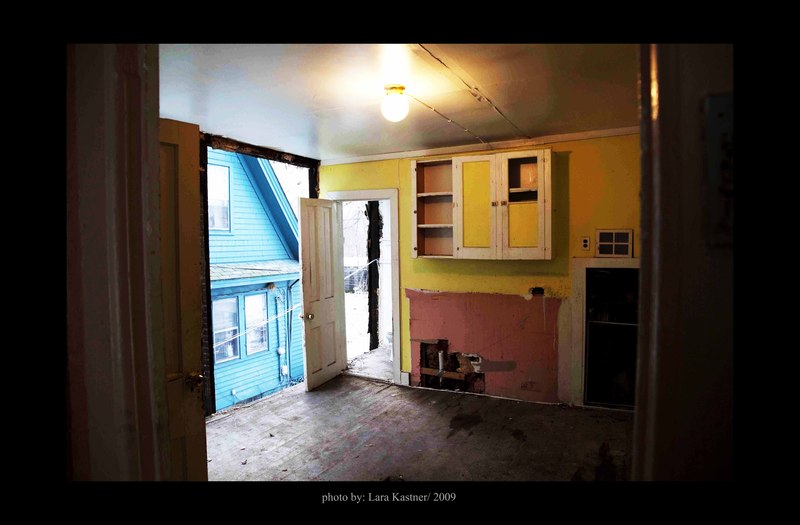

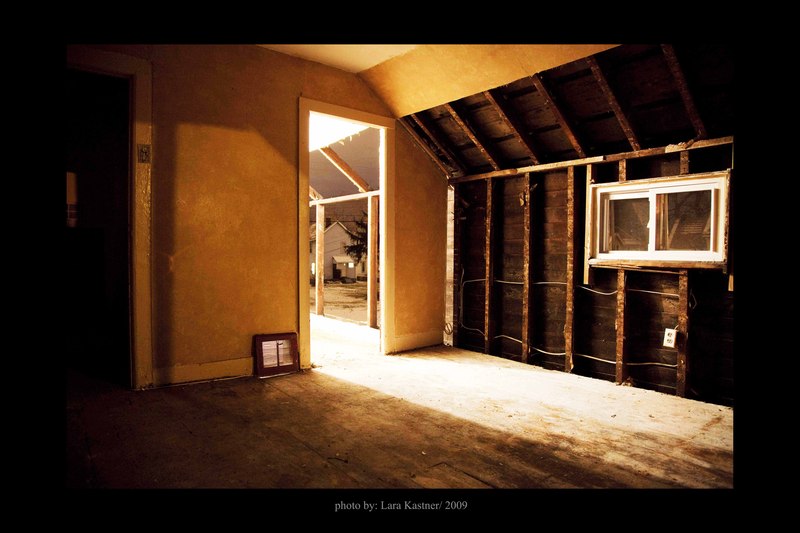

A house is an inanimate object, but also a receptacle for human hopes and dreams. Vestiges of past lives remain, even as a house sits empty and abandoned, awaiting the demolition crew. Martin Papcún’s work attempts to capture and honor the remaining traces of the people who once inhabited this disintegrating world. In Martin’s hands, a deconstructed house is an aesthetic object, a social statement, and the physical embodiment of painful demographic change.

In my work as a city planner, I am rarely exposed to the soulful side of the city’s deteriorated housing stock. Population decline and the on-going foreclosure crisis are manifested in sobering statistics and the physical realities of neighborhood disinvestment. Vacant houses have an immediate destabilizing effect on surrounding property values and tax revenues. Basic economic principles tell us that excess supply and weakened demand add up to a dysfunctional real estate market. The economic costs can be readily quantified, but the human costs are more elusive.

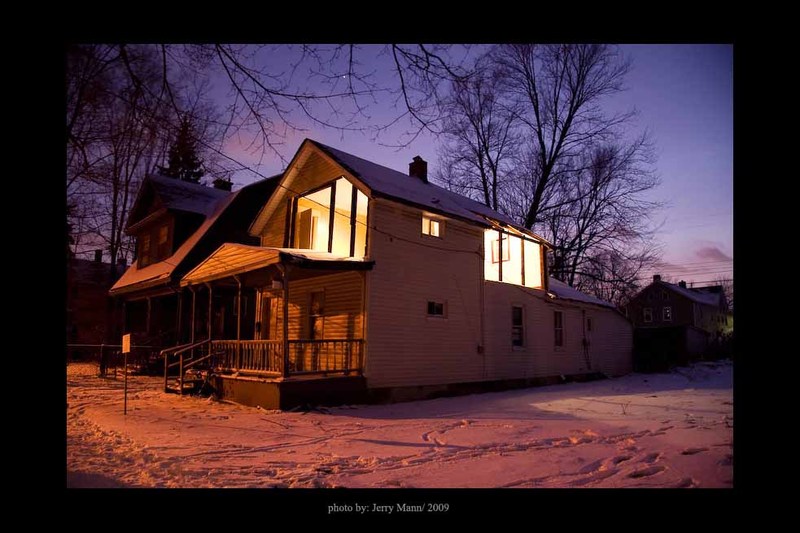

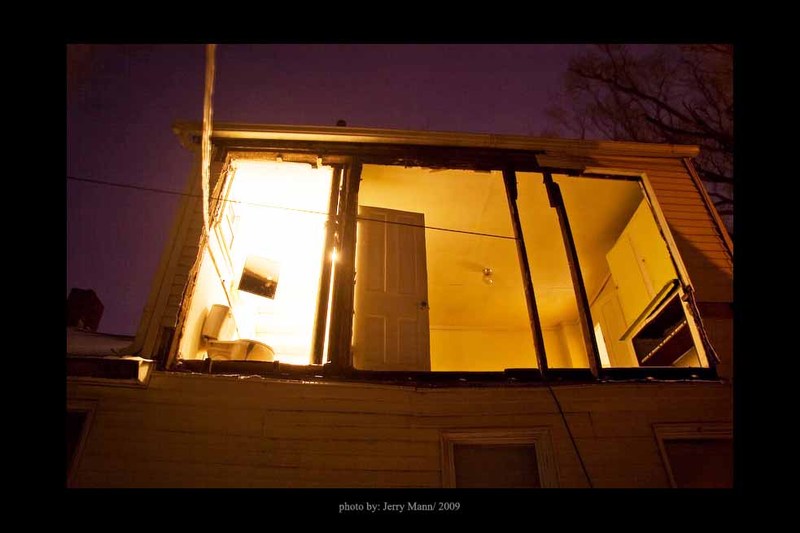

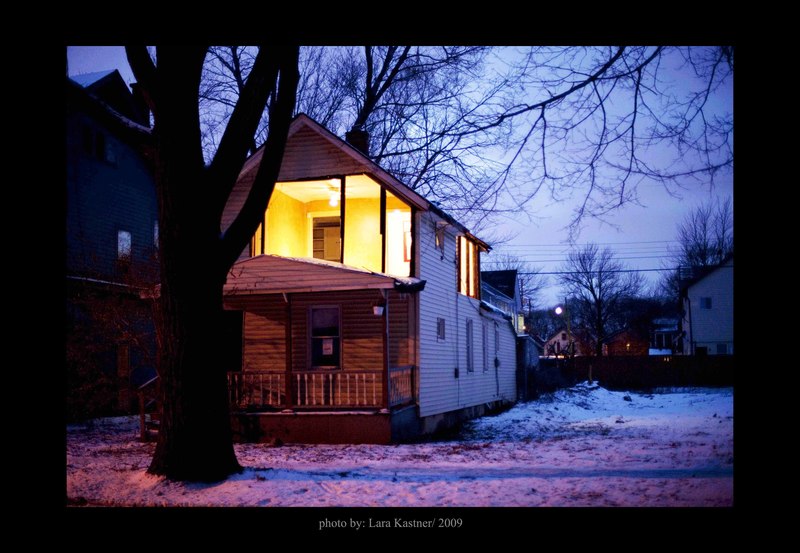

Martin Papcún’s work does not try to measure the human costs of urban vacancy. Instead, his installation on West 45th Street in Cleveland’s Ohio City neighborhood begins to personalize a frequently anonymous phenomenon. We are invited to peek inside a vacant house, temporarily re-animated by interior illumination that comes and goes in the night, suggesting a presence that is no longer present.

Planners and public officials in shrinking cities often attempt to create a similar kind of optical illusion. In Flint (Michigan), a city that has experienced tremendous population loss, landscape architect Joan Iverson Nassauer has devised a series of planting strategies for vacant lots that offer “cues to care.” A three-foot wide strip of turf grass provides a visual cue that a vacant site is being maintained. Beyond this orderly ribbon of grass, the vacant land lies fallow, with the chaos of re-emerging nature held in check by a valiant little lawn. In Cleveland’s Slavic Village neighborhood, the boarded up windows of vacant houses are painted with wistful domestic scenes—a cat sleeping on the window sill, pies cooling on the kitchen counter. The illusion is vaguely hopeful yet deeply sad. It’s as if we’ve recognized that we can’t restore the neighborhoods to their former vitality so we rely instead on palliative aesthetic devices for comfort and reassurance.

Ghostly memories of long-departed inhabitants loom large in the post-modern American psyche. “The Pedicord Apts,” a 1982-83 work by assemblage artists Ed Kienholz and Nancy Reddin Kienholz explores this theme with particular poignancy. The installation is part of the permanent collection of the Frederick R. Weisman Gallery at the University of Minnesota, is a reconstructed corridor from a former residential hotel that was demolished in Spokane, Washington. The installation surrounds viewers in a world of seediness and despair. You can’t help but imagine what might be taking place behind the closed doors of this dimly lit passage, a place of shabby but indelible humanity that feels inhabited somehow—a very convincing illusion.

Martin’s installation, though also illusory, provides an objective and quiet framework for confronting vacancy and loss. Instead of placing visitors in a transplanted environment like the Pedicord Apartments, he creates his installation in situ—engaging the neighbors and immersing visitors in a living display of the city’s robust past and tenuous future. When we look into his deconstructed house, it is familiar and tangible. We are absorbed into an imagined narrative. Who lived here? Where are they now? What happened to this ordinary little house and how was it inhabited during all those years when its walls were still intact? Those of us who left the city long ago are reminded that we play a part in this evolving story. We are eavesdroppers and voyeurs, returning to the scene of a crime in which we are fundamentally complicit.

When he is not deconstructing vacant houses in Cleveland, Martin is an accomplished jewelry artist in his native Prague. His jewelry resonates with the same themes as the West 45th Street installation—chambers of a home and chambers of the heart, what we take with us and what we leave behind. His work exerts an irresistible pull for the homesick as we attempt to reconcile our own memories of the places we come from, both real and imagined.

Theresa Schwarz is a senior planner at Kent State University’s Cleveland Urban Design Collaborative. She founded the CUDC’s Shrinking Cities Institute in an effort to understand and address the impacts of persistent population decline and large-scale urban vacancy.

Theresa Schwarz

/ http://www.spacesgallery.org/project/w-45th